Field notes from a hike up spectacular Arkle in Sutherland. With its fascinating geology and exciting ridge scramble, this is easily one of my favourite hills in Northwest Scotland!

FYI: This post contains affiliate links. If you make a purchase through one of my links, I might earn a small commission. Thanks for supporting the journey!

Trip essentials

These are my personal notes and are here to give you some inspiration for your own journey – they shouldn’t be used as a guide! If you’re heading to the hills, make sure you or someone with you has solid map reading and navigation skills. You’ll find links below to relevant maps and resources to help you plan your own adventure. Have fun and stay safe out there!

- Starting / Finish Point: Parking area off the A838 (View in Google Maps)

- Total Distance: ~16km

- Total Ascent: ~990m

- Terrain: Good track to start; then steep rocky ground with occasional paths; exposed ridge with some straightforward scrambling required on sometimes slippy quartzite rock

- Maps: OS Explorer Map 445 / Foinaven and Ben Hope Harvey Map

- View GPS on OS Maps (this is the route I took, but it’s just an indicator—not to be followed exactly. Paths on Arkle are unpredictable and often disappear, so your route will most definitely differ. Strong navigation skills are essential)

- Useful book(s): Rock Trails Highlands

- View this route and more in our Interactive Route Map

For route specifics, visit walkhighlands – for the geology lovers, Rock Trails Highlands has a superbly detailed chapter on all the geology you can see along the way. Here are my personal notes from the day…

Arkle Field Notes

Having been up Arkle before in totally murky, midgey conditions, I took the chance on 25 October 2024 to try Arkle again. We’ve had heavy winds and rain for days, and a similar outlook for the future. This particular Friday was a window of calmer winds (but potential for cloud), so I decided to see if Arkle would give me some views this time. Though the summits were in mist, I had some wonderful Highland mountain drama along the way.

The initial approach to the hill is a pleasant, fairly level easy track to an enchanting woodland (see above) where I once camped on a separate adventure years ago. (You can use a bicycle to make these first and last few kilometres go by faster).

The journey to the first top is a long steep slog – I took the approach that followed closer to the ridge. Walkhighlands takes a slightly different route, following the Allt na Dige Moire where there is a more well-defined path. I found this previously to be a bit of a slog with all the dramatic views cut off by the surrounding hills. The ridge approach has some intermittent paths, but they’re easy to lose. However the views of Ben Stack and beyond to the sea are good company for the long steep climb to the rocky top.

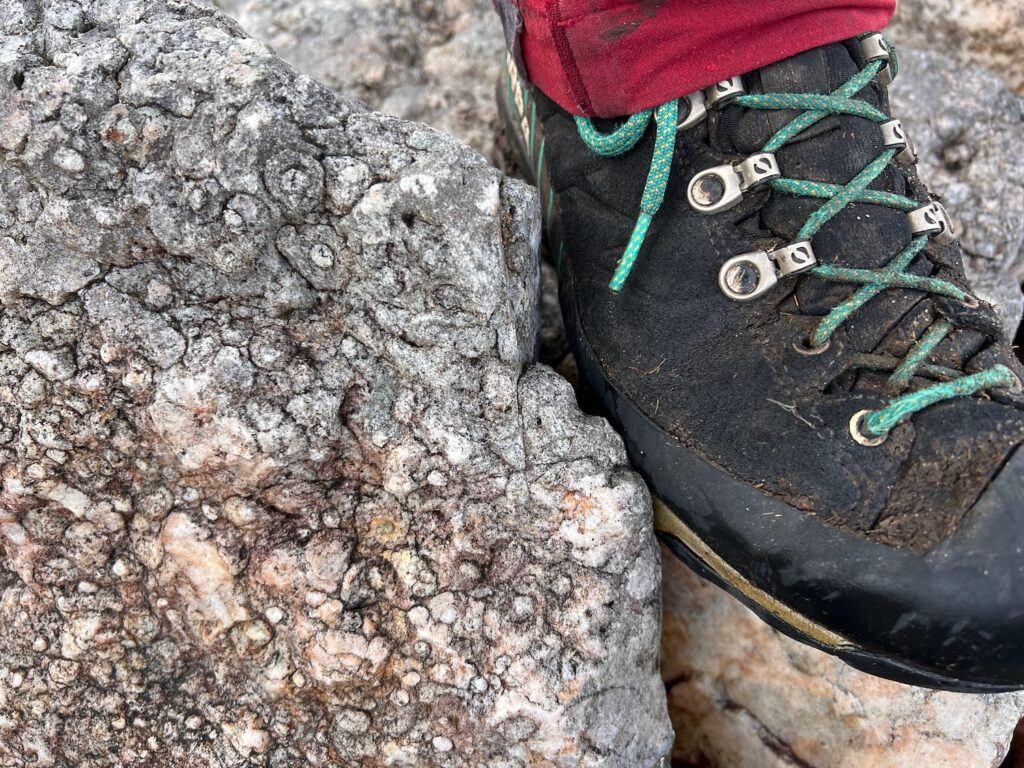

Over views can be found underfoot. Arkle is literally covered with “pipe rock”, fossilised burrows of ancient worms! More on this below…

Arkle has two tops – the first top at 758m is broad flat area of broken quartzite and a cairn. We had no views at the first top except for a sandwich! Things really get interesting as you move onwards to Arkle’s high point at 787m. The journey is an exciting ridge walk with a little light scrambling (take care as the rocks can be slippery when wet!). This was definitely the most exciting part of the day and fun even in poor visibility. Lucky was a scrambling superstar.

A ridge so nice you get to do it twice – Arkle is a there-and-back walk as there’s no practical way down the other side. So after a quick selfie at the top, we returned again over the ridge and back down the hill.

Arkle Geology Highlights To Look Out For

Visible Geology of The Moine Thrust

Arkle’s geology features a dramatic age contrast: Cambrian quartzite (about 500 million years old) sitting atop ancient gneiss rocks that are up to 3 billion years old. The divide is clearly visible on the approach. This creates a striking geological narrative, showcasing how “young” Cambrian rocks are in comparison to the ancient gneiss. This is what’s called an unconformity (learn more: what is an unconformity?).

Arkle and the surrounding peaks, including Foinaven, belong to the Moine Thrust Zone, where tectonic forces have pushed massive rock layers up and over each other. Look for the distinct slanted layers of quartzite, especially around the quartzite-gneiss boundary, a clear marker of these insane ancient earth movements.

Glacial Sculpting

The north-eastern sides of Arkle feature the impressive Am Bathaich, a deep glacial corrie, pictured above. These steep-walled, U-shaped valleys are the result of ancient glaciers carving into the rock during the last ice age. Mental!

‘Pipe Rock’ Fossils

“What’s up with all these rocks with spots?” I asked Mark on our last trip up Arkle. Ah-hah moment: “It’s the pipe rock!!!”

A feature of Arkle’s quartzite is “pipe rock”, vertical cylindrical tubes or “pipes,” which are actually ancient burrows made by marine worm-like organisms living in a shallow sea more than half a billion years ago. They’re visible as tiny, white tubes less than 1 cm in diameter and can be spotted in both large outcrops and smaller individual rocks as you ascend. They’re literally everywhere on Arkle as you get to the higher slopes! And here’s why…

Imbricated Quartzite

It’s believed that the pipe rock occurred at all the same level back in the day. Now it’s all over the place because of the collision of two continental plates. The original pipe rock was broken, and then thrust on top of itself over and over again. This repeated piling of rock on top of itself is called ‘imbrication’, a common feature of rocks in NW Scotland. You can also find them in the Appalachian Mountains and Norway – also caused by the same tectonic events that shaped the Highlands (learn more about the Caledonian orogony).

Quartzite Pavements

Higher up the slopes, the rock layers reveal exposed “quartzite pavements.” These areas, marked by tilted bedding and a sparse covering of vegetation, are evidence of ancient sedimentary layers from when the region was once a shallow sea over 500 million years ago.

The Cambrian quartzite in this part of Scotland has a very high proportion of quartz silica, a stable mineral that doesn’t readily break down into the minerals needed for soil growth and vegetation. Hence why Arkle is such a rock-fest!

Erosion and Freeze-Thaw Patterns

The reason for all the broken up rocks is freeze-thaw, millions of years of erosion and periods of freezing and cooling, which have exploited the natural joints in the rock. Loose chunks of quartzite scattered along the path are remnants of this slow geological weathering.

Gallery

Garmin Data

Source: Garmin Instinct 2 Solar. Download GPX on OS Maps.

Leave a Reply